Making decisions in time

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Table of Contents

Background

Development

Implementation

Analyses

The Future

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Background

It started with a simple question: “Why compose at all?”

At the time I was working on what would later become iminlovewithanothergirl.com and was trying to figure out how to deal with composing for myself as an improvising solo performer using a new/invented instrument which is difficult to reproducibly control. This marked a big shift in my compositional thinking. I began moving away from precomposing discrete gestures and started focusing on pure improvisation. I carried on this line of thinking through multiple compositions and projects over the next three years and eventually produced a framework for thinking about improvisation – making decisions in time.

The dfscore system, a realtime dynamic networked score system, allowed me to explore the middle ground between composition and improvisation and was the first project in which I implemented a technical solution to deal with some of my improvisational (/compositional) concerns. Using the dfscore system I composed a number of improvisatory pieces exploring the dynamics of group interaction and performance, specifically examining synchrony as a compositional parameter. This technical approach to a compositional/creative concern is something that would be developed further in later pieces and projects.

[su_pullquote align=”right” class=“”]When and what decisions were being made became an area of focus for me.[/su_pullquote]

Shortly after conceiving the idea for my series of compositions Everything. Everything at once. Once. I realized that while improvising I would focus on the singular moments in time when I would make decisions. I did the same when I listened to other people improvising. John Stevens talks about this in this book when he says “[l]istening, context, and the ability to make decisions are of prime importance in improvised music” (Stevens 1985). Underneath the layers of aesthetics that indicated performers’ styles, timbral tastes, and performative tendencies, I would hear skeletal frameworks of decisions being made, similar to the segmentation described by Clément Canonne and Nicolas B. Garnier in this paper. Lê Quan Ninh describes a similar sentiment in this book where he describes improvisation as something that “seems to bypass aesthetics”. I would listen and relate to that layer more than the surface/perceptual ones. That layer made up the conversation, the sport, and the interaction in the music for me. When and what decisions were being made became an area of focus for me.

These compositions and projects were part of a trajectory; I was moving away from notated music in general and towards an intellectually supported improvisational practice. Because of this, I wanted all of these developments to focus solely on the concerns and interests of improvisers, as opposed to bringing compositional thinking into the realm of improvisation. This was inspired by John Zorn‘s Cobra, in which Zorn prescribes mainly behaviors and relationships.

I never specifically told anyone anything. I set up rules where they could tell each other when to play. It is a pretty democratic process. I really don’t have any control over how long the piece is, or what happens in it (Duckworth 1999).

[su_pullquote align=”right” class=“”]Conduction and Sound Painting are fundamentally modeled after a composer/performer hierarchy.[/su_pullquote]

I view the compositional approach in Cobra as music by improvisers for improvisers. This is in contrast to the more top-down approach of something like Butch Morris’ Conduction or Walter Thompson‘s Sound Painting. Both of those compositions—or rather, approaches to music—as they extend beyond a single composition, are fundamentally modeled after a composer/performer hierarchy. The conductors of these systems generally prescribe content, with varying degrees of specificity. Even built into the titles are the hierarchies of the conductor and the painter, of a single creator using the performers as their instruments/paints. I view this approach to composition as music by composers for improvisers.

The approach I wanted to take involved a visualization of the decisions, something to allow me to view events that happen in time in an out of time manner. This would hopefully allow me to find patterns that I would not have seen or heard otherwise, as is often the case when one transforms information into a non-native data type. In this paper by Michael A. Nees and Bruce N. Walker they talk about the usefulness of sonification, or the creation of “auditory graphs”, in aiding the understanding of large amounts of scientific data. In a more musical context Pierre Couprie argues in this paper that a visual representation of musical information can augment the listening experience in an aesthetic way, in phase with the tradition of acousmatic listening scores.

[su_pullquote align=”right” class=“”]These kind of visualization can offer valuable insight into the compositional process and underlying thinking.[/su_pullquote]

Notation, along with all of its strengths and shortcomings, allows you to see and verify things in the listening experience. Things are generally notated in a manner that is charged with meaning, with things like bar lines and beams creating material divisions. Non-notated music does not really have a parallel to this. There are some listening scores (Hörpartitur) that have been created after the fact for electronic music, such as Rainer Wehinger’s listening score to Ligeti‘s Artikulation. Wehinger, a graphic designer, created the listening score more than a decade after the piece was originally composed in 1958. More recently Yotam Mann has come up with an audio descriptor-based visualizer for Ableton Live called Artikulate, though it lacks the level of detail that Wehinger’s score contains. These kinds of visualizations, although aesthetically charged, can offer valuable insight into the compositional process and underlying thinking, such as formal considerations and polyphonic treatment of material.

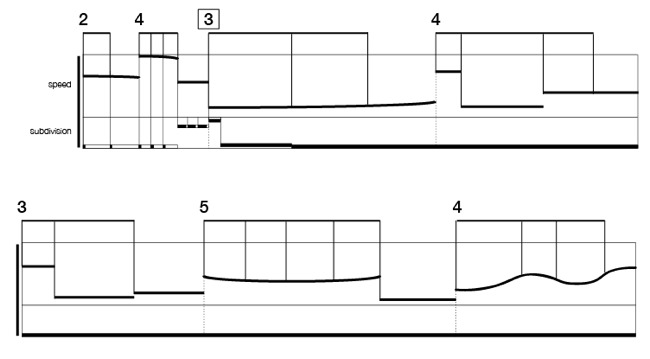

A similar approach to visualizing an improvised performance, albeit with an emphasis on rhythm/time, is Aaron Cassidy‘s analysis of the first 45 seconds of Peter Evans‘ Sentiment. Cassidy’s analysis focuses on the speeds, groupings, subdivisions, and durations of Evan’s improvised performance. You can clearly see the defined phrases and groupings, particularly in the long sustained note that makes up most of the example.

And here is the first 12 seconds lined up with a spectrosonogram.

You can hear the example and learn more about Cassidy’s approach to rhythmic notation in his lecture on Imagining a Non-Geometrical Rhythm.

Both of these examples add additional analytical breadth into the inherently non-visual compositions that they are made for. However they require a lot of time and effort to produce and are therefore impractical to produce for multiple pieces. There have been some software tools developed to make this process easier and allow more in-depth analysis, but the process is still laborious. Additionally, they are largely presented as purely graphic representations that don’t allow for additional analyses based on data points in the analyses.

The approach taken by Canonne and Garnier centers on formal segmentation of material based on a reflective analysis by the performers. This approach offers a performer-centric analysis, focusing on the perception of changes in material as experienced by each performer. This graph from the paper illustrates the perceived segmentation from each performer’s perspective.

The approach used by Canonne/Garnier is not without its shortcomings. Basing analysis purely on audio detaches the visual empathy from the reflective analysis and focuses primarily on segmentation as the primary analysis metric. This is unsuitable when the material being analyzed is non-aural, coming in the form of decisions. Additionally, the focus on discontinuity in formal segmentation, although significant in group improvisation, is of less importance in solo performance.

[su_pullquote align=”right” class=“”]These discussions lead to ideas which inform the next improvisation, creating a meta-dialog/feedback loop over a series of rehearsals.[/su_pullquote]

Some of my approach is also grounded in a practice of verbal reflective analysis during rehearsals with several improvisers I regularly play with, something that is not uncommon in improvisation, as can be seen in Matthew Bourne‘s excellent Insights on Montauk Variations. This can include a wide range of topics such as moments of heightened interaction, certain emergent textures, the overall form, and specific technical points. I have found this practice of analysis/reflection critical in the development of improvisational skills and sensitivity, particularly when done with performers you have worked with for a long time. These discussions often lead to new ideas which then inform the next improvisation, creating a meta-dialog/feedback loop over a series of rehearsals.

Here is Glitch Beat, one of the Battle Pieces which emerged from such verbal reflective analyses (texture, repetition, internal/external learning, tangent).

Coming up with this framework for thinking about improvisation has given me some insight into how my decision making apparatus works in time. I can see explicit patterns and tendencies in the way my decisions are structured. More importantly, tuning in to that decision framework has let me draw, and articulate on, a conceptual circle around that creative plane, a meta-creativity that I explore in other pieces and projects. Additionally, assisting other performers with their own improv analyses (as outlined below) has given me a deeper understanding into other’s improvisational thinking as well.

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Development

The day after filming the first Everything. Everything at once. Once. performance I watched the videos over and over again, focusing on my decisions, and started writing down what I remembered thinking from moment to moment using video-cued recall. In watching myself I found that I was able to empathize with what I was thinking at any given time as a structural “focal point”, to use Canonne’s terminology from this paper. The video proved invaluable in this regard, as trying to base this kind of decision-centric analysis on audio alone would have led me to focus only on the sounding results instead of the decisions underlying them. Using a video-cued recall technique also helps to “reduce the effects of distortion in self-report data collection” as outlined by Anne Miller in this paper.

After writing down these raw decisions, an excerpt of which can be read below, I found that they fell into certain categories. These were Material, Formal, Interface, and Interaction, and I defined them as follows:

- Material – Decisions dealing with manipulations of local, sonic materials. These can come in the form of instrumental behaviors or general development, and are open to context and interpretation.

- Formal – Decisions dealing with form and transitions.

- Interface – Decisions dealing with instrument, ergonomics, technology, and performance modalities.

- Interaction – Decisions dealing with how materials interact, primarily with simultaneous materials (as opposed to Formal decisions), but not exclusively so.

[su_pullquote align=”right” class=“”]The streams are a reflection of the type of musical thinking that I engage with while improvising.[/su_pullquote]

This categorization happened after the fact, based on the types of things I had written down. As such, it is a reflection of the type of musical thinking that I engage with while improvising. The categories themselves are not exhaustive, for example there is no theatrical or non-musical category, but the framework and analysis tools allow for an openness in scope which can be applied to other approaches to improvisation/music.

Since they would happen simultaneously, each one of the decision making categories was called a decision stream. The use of the term streams is a nod to stream of consciousness writing, and to the groupings and streams from auditory scene analysis which poetically and practically suits this type of analysis.

The process of creating an analysis begins with filming an improvised performance, preferably with a fixed position high-quality camera and instrument-appropriate microphones. The performer then watches their improvisation back, pausing, replaying, and rewinding, writing down all of the decisions they can remember along with the time they happened into a spreadsheet. The process is time consuming; it can take several hours to go through a 3-4 minute video/performance. Once the initial timing/comments are written down the performer sends the timing/comments to me for streaming. Since I have the most experience streaming, I find this approach works best as it provides a more consistent streaming, particularly since there can often be some ambiguity as to the stream that a decision belongs to (e.g. a Material decision that has Formal repercussions). The streamed analysis is then sent back to the performer for them to verify they are happy with the streaming. Click here to read a more detailed description of how create an analysis for the system.

Everything. Everything at once. Once. (3c):

[su_pullquote align=”right” class=“”]I discovered that the ability to empathize with one’s own decision making apparatus, while watching a video, dissolves very quickly.[/su_pullquote]

So far I have analyzed four of my own improvisations and assisted in the creation of several other performers’ analyses. For my own performances I analyzed all three videos from my initial Everything (1) set of videos, as well as a performance using reactive DMX lighting. In these analyses I discovered that the ability to empathize with one’s own decision making apparatus while watching a video dissolves very quickly. By their physiological nature, episodic memories such as these, although quickly stored, are “highly susceptible to distortion, especially with repeated recollection” (Snyder 2001). I analyzed (1a) the day after the performance, then (1b) the day after that, and finally (1c) a day later. By the time I got to the third day, I found that I could only really infer what I was thinking by observing the sounding results of that thinking (i.e. what I was doing) and inventing a “narrative fallacy” (Kahneman 2011). As a result, the data for the third analysis is quite different from the first two. I have kept it, but I will likely use it as a control to show what ‘bad analysis’ looks like.

I felt that in order for this type of analysis to be meaningful, I would have to be brutally honest about my thinking, even if it was not flattering. Here is a segment of the raw, unedited analysis for Everything. Everything at once. Once. (1b):

- 0:05 – decide on ‘soft’ entry

- 0:08 – begin cymbal rubbing pattern/rhythm (in contrast to attack-based playing method of previous piece)

- 0:10 – pattern too regular – alter steady rhythmic pattern to create variety (slower/faster)

- 0:15 – formal brain calls for further breaking of pattern. adding interruption/pauses

- 0:20 – decide to use cymbal press/pauses to coax electronic changes

- 0:25 – shift to change of playing surface to engage electronic sounds – it does not happen

- 0:28 – formal brain calls for a gesture to return to rubbing pattern, now fused with rubbing gesture

- 0:35 – electronic sounds start changing and becoming more interesting – pause to listen

- 0:37 – return to playing with even more erratic gestures

- 0:39 – incorporate acoustic friction sound (from previous explorations/pieces)

- 0:42 – formal brain calls for shift. fade out amp

- 0:45 – return to rubbing gesture, but more erratically/quickly

- 0:47 – decide overall sound is too weak for energy level, decide to bring amp back in on smaller gesture

I then separated them into individual streams. In cases where decisions could have potentially fallen into multiple categories it was occasionally difficult to determine the most dominant stream. Here is the same section of the analysis with the streams attached and the wording cleaned up slightly:

- 0:05 – Material : Decide on ‘soft’ entry.

- 0:08 – Material : Begin cymbal rubbing pattern/rhythm (in contrast to attack-based playing method of previous piece).

- 0:10 – Material : Pattern too regular – alter steady rhythmic pattern to create variety (slower/faster).

- 0:15 – Formal : Formal brain calls for further breaking of pattern. adding interruption/pauses.

- 0:20 – Interface : Decide to use cymbal press/pauses to coax electronic changes.

- 0:25 – Interface : Shift to change of playing surface to engage electronic sounds – it does not happen.

- 0:28 – Formal : Formal brain calls for a gesture to return to rubbing pattern, now fused with rubbing gesture.

- 0:35 – Interaction : Electronic sounds start changing and becoming more interesting – pause to listen.

- 0:37 – Material : Return to playing with even more erratic gestures.

- 0:39 – Material : Incorporate acoustic friction sound (from previous explorations/pieces).

- 0:42 – Formal : Formal brain calls for shift. Fade out amp.

- 0:45 – Material : Return to rubbing gesture, but more erratically/quickly.

- 0:47 – Interface : Decide overall sound is too weak for energy level, decide to bring amp back in on smaller gesture.

Click here to download the complete raw file. / Click here to download the complete edited file.

Feel free to follow along with the video. Everything. Everything at once. Once. (1b):

[su_pullquote align=”right” class=“”]Outlining these decision streams created a mental framework that allowed me to think and talk about my improvisation.[/su_pullquote]

In the time between coming up with the system and creating the initial analyses and visualization tools I found that my ability to improvise had improved. Outlining these decision streams created a mental framework, outside of data analysis, that allowed me to critically think and talk about my improvisation. This would materialize in a performative setting by allowing me to focus on the types of decisions I was making, and when they should happen, in a kind of meta-formal capacity/way.

This meta-awareness is something that has spanned many of my compositional and creative explorations over the last three years. Starting with form in iminlovewithanothergirl.com and later memory in ialreadyforgotyourpussy.com, I moved on to instrumentation (in a literal sense) in Everything. Everything at once. Once. There is also an element of a personal curation of performers in the dfscore pieces similar to Zorn’s approach in many of his compositions for improvisers (Cox and Warner 2004). This tuneable conceptual focus has let me individually focus on these different aspects of what I find interesting about improvisation and creative work in general.

The following video demonstrates some of these creative, conceptual, and formal considerations in an improvised solo performance.

Additionally, these thought processes influenced a number of compositions, specifically an amplifier, a mirror, an explosion, an intention and the Battle Pieces. an amplifier, a mirror, an explosion, an intention was the first piece that explicitly used the decision streams creatively as a part of the conceptual framework of the piece, and not solely an after-the-fact analysis tool. In the Battle Pieces, the impact of the system was more as part of a creative feedback loop. The analytical concepts informed several pieces which, in turn, informed the further development and implementation of the concepts.

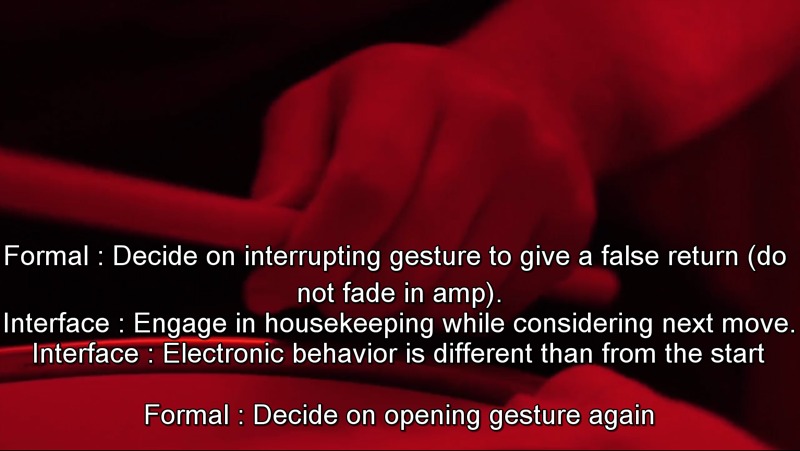

When I started to work on the technical implementation of the system I initially experimented with the idea of using video subtitles, with the SubRip file format (.srt), as the main way to view the analyses. A fellow PhD candidate, Braxton Sherouse, helped me create a ruby script that would take my raw text files and convert them into suitably formatted .srt files. This subtitle-based approach, although useful in areas with low decision rates, proved to be problematic in sections with a high density of simultaneous events. The video-based nature of this approach also made it impossible to view the information in an out-of-time manner, which negated many of the benefits of a notational/visualization graph and moreover didn’t allow statistical analysis of the data.

a screenshot of Everything (1a) at 34 seconds in showing an overload of information. Click to download the mp4/srt files.

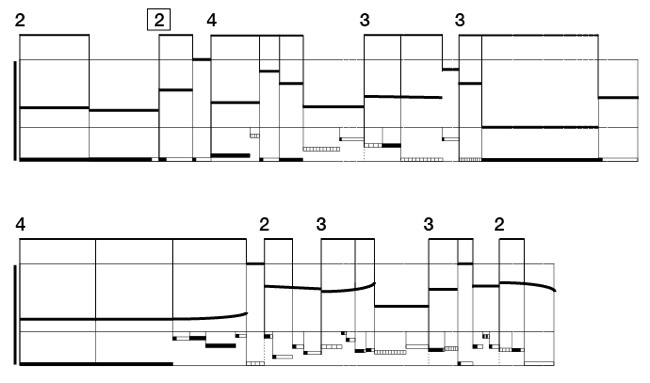

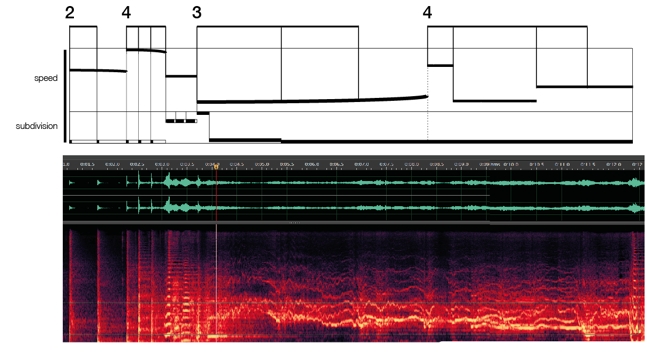

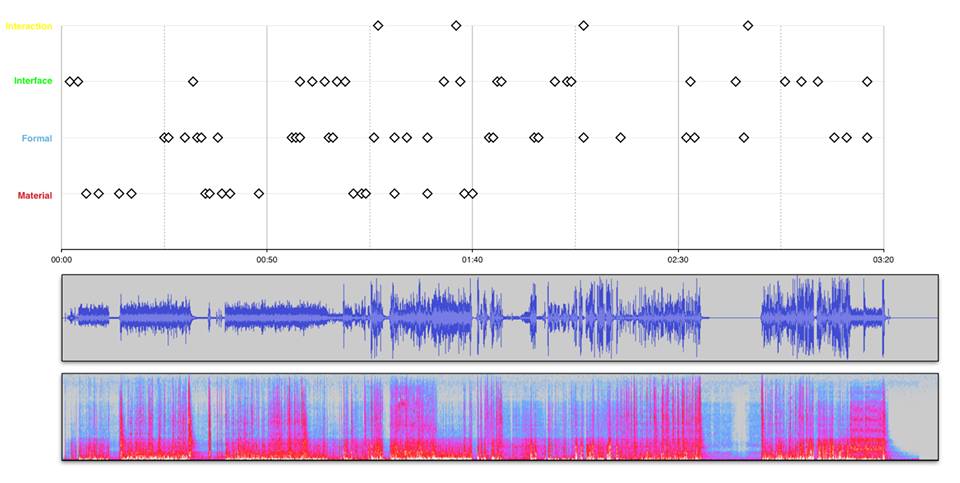

After finding the subtitle approach unsuitable, at least in its current incarnation, I decided to create a spreadsheet analysis using the data shown above (time, stream, comment). Once the data was in Numbers I began creating all kinds of graphs and charts from the data in search of relevant representations. I found that the most useful of these representations was the static constellation view, which shows the streams on one axis and time on the other. I later paired this up with a waveform and spectrosonogram to be able to reference what was happening sonically at those points in time.

Here is the original Numbers generated constellation view/analysis of Everything. Everything at once. Once. (1a):

graphic representation of Everything (1a) along with waveform and spectrosonogram graphics from Audacity

Using the raw numerical data I also produced activity rates within each stream, along with trend lines showing the overall trajectory of activity in the piece (or within each stream).

In addition to these static graph-based analyses I did some generic number crunching, calculating the minimum, maximum and mean for each stream. I also created a transition matrix to show how often each stream went to each other stream (e.g. Material going to Formal six times in the piece). These static analyses have already proved insightful, and I imagine they will provide an even deeper understanding once I have enough data to correlate between individual analyses. This should allow me to notice tendencies that I may have on a subconscious or even physiological level.

[su_pullquote align=”right” class=“”]These statistics fall in line with a theory I have that Material decisions are linked to language.[/su_pullquote]

These statistics fall in line with a working hypothesis I have that Material decisions are linked to language in their rate of activity and density. Since I seem to speak at a higher than normal rate, so it would be fitting that my Material decisions would be fast as well. The link between musical material and language is often discussed in a metaphorical sense, with language referring to aspects of musical syntax, general tone, or communication, but I suspect that the language we speak of while improvising, due to its created-in-time nature, is less metaphorical and more tied to the language center of the brain, and its cognitive functionality (Farber 1991). Currently there is lots of research in cognitive neuroscience about the language center (Broca’s area) and how it relates to other, non-linguistic, aspects of cognitive function. In reference to this study on the subunits of Broca’s area and its results Hagoort, a professor of cognitive neuroscience, states that “the language-selective region might play a role in the perception of music”, although he adds that this was not specifically tested in the study (Trafton 2012).

So with these static-spreadsheet based analyses in hand, I decided I wanted something more interactive, musically useful, and easier to produce. Many of the metrics I produced (such as transition types/amounts) had to be calculated manually for each analysis I produced, which was both tedious and error prone.

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Implementation

Even before creating the Numbers-based version of the analysis, I spoke to Braxton about how to best visualize this kind of analysis data since I was very much impressed with his analysis of Xenakis‘ Theraps. The ability to zoom in and out of a section of material dynamically allowed for an insightful overview of material, leading to the discovery of relationships that might have otherwise been missed. Although his analysis was created in C++, he recommended the D3 library for Javascript as it is (relatively) easy to use.

I was also very much inspired by Jack Schaedler‘s amazingly well put together introduction to digital signal processing, and David Pocknee‘s article on keyboard usage in Beethoven Sonatas. Both of these used the D3 library in a useful and informative way. I looked through the D3 documentation and found that, even though I had used javascript in the past and had done the Javascript course on codeacademy.com, putting together something complex in D3 was a bit beyond my technical chops. Enter Tom Ward.

I contacted Tom and asked him if he would be interested in putting together a better version of what I had built. Luckily, he was. Tom, in addition to being a programmer, is an improvising saxophonist, so he was able to not only understand the motivations and functionality of this kind of framework, but also to contribute to how it could best be implemented.

Since I did not personally develop the software for the system I asked Tom if he could talk about how he approached the project, why the specific technologies were used, how the back-and-forth-ness of the development worked, and anything else he thought might be interesting. The following pseudo-interview is his response.

How you approached it

With any software project, the first job (& often the biggest challenge) is to figure out what the user wants. In this case, it was easy as Rod had a strong concept of where he was aiming – he’d already produced what was essentially a static prototype of the project using a spreadsheet & some manual calculation.

We started with a bit of discussion in which I checked with Rod some of the meanings, definitions, preferences and assumptions in his static prototype whilst also trying to de-scope anything that wasn’t core to a first working dynamic prototype. Then I quickly got to work throwing together an alpha version so that I could get the feedback loop started – not a formal agile software development process, but definitely inspired by that philosophy.

Why these technologies?

It was taken as a given that the project would be web-based, as that provides for putting it in front of the widest audience. There are many great modern tools around for building dynamic, interactive data visualisations on the web, and we had no specific requirements that would have benefited from building the software as a native app. With that as a given, the language of choice had to be JavaScript as we wanted something interactive to be running in the browser, and then it was an easy choice to commit to the D3 ecosystem to provide support for data wrangling & graphical whizziness.

In order to get up & running quickly, I decided to start with a charting library to sketch out the simplest of Rod’s graphs. Here there were a few choices, but dimplejs caught my eye for good-looking examples that covered the particular use case required. Dimple proved to be easy to work when getting started, and I hadn’t really intended for it to end up in the end product, but it exposed enough raw D3 that I could easily customise, extend, & enhance it to provide Rod’s required custom functionality, so it stayed.

The waveform display was a little more challenging, but some googling revealed this BBC R&D project that provided the required basic functionality that I could build on. However, as a BBC internal project on which peak.js is built, I started to find myself reimplementing some functionality from peaks.js on top of waveform-data.js.

How the back-and-forth-ness of development worked

From a practical point of view, I was developing on a local web server on my laptop. This allowed a very tight feedback loop & allowed me to do quite a bit of development work “offline” whilst travelling around the UK on trains with poor internet connections. This was my “inner loop”, involving building features, experimenting with UI layouts, and bugfixing, which was all committed to my internal git repo as I went along. I would then periodically (at stable points) run the “outer loop” by uploading the latest development code to my external webhosting before soliciting feedback from Rod to see what’s working & what needs changing. In some cases having an external critic forced me to get features to a higher level of polish than I might otherwise have done, an example of which was the playhead rendering code. I had a working naive implementation of some code, and I had just started to learn to accept its somewhat poor performance when I got feedback from Rod saying “the playhead’s a bit juddery” that forced me to rework it, leading to much improved performance.

Anything else you think might be interesting

Hmm, not sure, my git log is possibly interesting…

Working back and forth over a few weeks Tom put together something interactive, compact, and significantly better than what I had cobbled together in a spreadsheet. It is largely built around the D3 library for Javascript, but uses some additional web technologies to allow linked audio playback and dynamic recalculation of zoomed in data (dimplejs, regression-js, JQuery, waveform-data.js). These are all open source technologies, fitting in well with the sharing ethos I have.

Here is the playback/zoom section, along with the no-longer-static constellation view.

[su_pullquote align=”right” class=“”]One of the biggest differences in this new version is the interactivity.[/su_pullquote]

One of the biggest differences in this new version is the interactivity. You can hover over each point to see the comment for that specific decision as well as the specific time stamp for that point. When more than one decision happens at the same time the point is slightly larger, allowing you to still take in the rate of activity on that stream. The waveform display is generated dynamically from the provided audio file and you can playback audio by hitting the play button (or space bar). To play from a specific decision or point in the waveform you can simply click on the point or anywhere in the waveform. The long thin vertical playhead moves through the graph, showing the current position in both the waveform and constellation displays. The ability to interact with the analysis in this dynamic way gives a more nuanced and complex understanding of data, as can be seen in the analyses presented below.

The top part of the page stays in place as you scroll down the analysis page and acts as a sort of transport, allowing you to start/stop playback as well as zoom in to a specific section of the piece. Everything dynamically adjusts when you resize the viewable area.

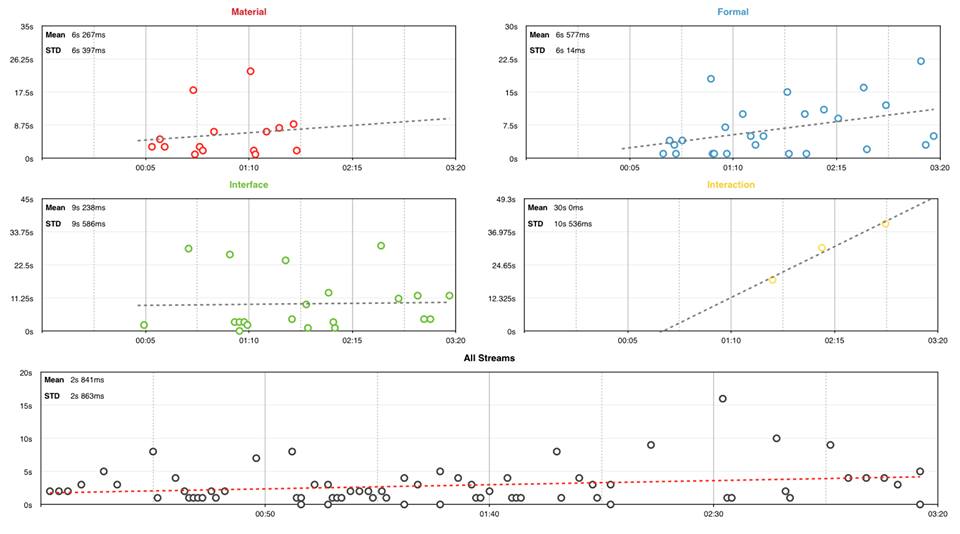

There is also a large decision-duration trend chart view which allows you to see the durational trends for the overall piece, or within any given stream. It looks like this:

Everything, including the trend lines, recalculates when a new selection is made in the top part of the window. These trend lines, showing the length of time between individual decisions, give some insight into the general rate of activity in any given improvisation, as well as the trajectories therein.

[su_pullquote align=”right” class=“”]These metrics can shed insight to the creative apparatus behind the improvisation.[/su_pullquote]

Finally we have the static metrics of minimum, maximum, median, mean, standard deviation, activity, and transitions. All of these are calculated automatically, and they dynamically recalculate whenever a new selection is made in the top part of the window. These metrics are useful in determining overall tendencies and rates of activity, which can shed insight into the creative apparatus behind an improvisation. These calculations will also be useful across multiple analyses of the same performer, or as compared to other performers, in identifying large scale tendencies which may have physiological groundings, something that I will explore in the in-depth analyses undertaken below.

Activity Summary

Transition Matrix

Duration stats per stream

The implementation, as it currently stands, is a robust and complex analysis tool that can provide immediate insight into one’s improvisational practice, underlying psycho/physio-logical tendencies, and creative arc over time. The system can also be used as the basis of more in-depth musicological analyses of music as will be seen in the next section.

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Analyses

In this section I will use the improv analysis framework and tools to provide an in-depth analysis of two improvisations (by Pierre Alexandre Tremblay and myself) as well as present all of the analyses gathered so far, including tangential analyses of an Upright Citizens Brigade‘s ASSSSCAT! comedy improvisation and Bryn Harrison‘s reflective listening of Feldman‘s Triadic Memories.

Here is the complete list of analyses:

- Sam Andreae – Electronics improvisation

- Sam Andreae – Tenor Sax improvisation

- Gemma Bass – Violin improvisation

- David Birchall – Guitar + Objects improvisation 1

- David Birchall – Guitar + Objects improvisation 2

- Jorge Boehringer – Electronics improvisation 1

- Jorge Boehringer – Electronics improvisation 2

- Matthew Bourne – Piano improvisation 1

- Matthew Bourne – Piano improvisation 2

- Greta Buitkute – I was thinking betula pendula

- Rodrigo Constanzo – Everything. Everything at once. Once. (1a)

- Rodrigo Constanzo – Everything. Everything at once. Once. (1b)

- Rodrigo Constanzo – Everything. Everything at once. Once. (1c)

- Rodrigo Constanzo – Light Vomit

- Simon Fell – Double Bass improvisation 1

- Pete Furniss – the outside-in side / 1

- Pete Furniss – the outside-in side / 2

- Jay Gilligan – Improvisation Nov. 28, 2015

- Angela Guyton – Amplified Canvas improvisation

- Anton Hunter – Guitar + Pedals improvisation

- Keith Jafrate – Chimes

- Lê Quan Ninh – Percussion improvisation 1

- Simon Prince – 15.11.2015

- Cath Roberts – Baritone Sax improvisation 1

- Tullis Rennie – Trombone improvisation 1

- Tullis Rennie – Trombone improvisation 2

- Chris Sharkey – Guitar + Pedals improvisation

- THF Drenching – The Invention of Duct Tape

- THF Drenching – The Eventual Skimming of Black Milk

- Sam Thursfield – number8

- Pierre Alexandre Tremblay – Bass + Laptop improvisation 1

- Pierre Alexandre Tremblay – Bass + Laptop improvisation 2

- Otto Willberg – all weather

- Upright Citizens Brigade – ASSSSCAT! (Buzzards scene)

- Morton Feldman – Triadic Memories (Bryn Harrison’s reflective listening)

Analysis 1 – Rodrigo Constanzo – Everything. Everything at once. Once. (1a)

The first in-depth analysis will be of Everything. Everything at once. Once. (1a). Everything. Everything at once. Once. is a series of improvised pieces that focuses on the curation of instruments as the prime compositional material. Everything (1a) is centered around a pair of snare drums and some cymbals/objects. It also incorporates the ciat-lonbarde Fourses synthesizer which I have modified with my DIY Electric Whisks.

This is what the setup looked like shortly before filming:

The full set of instruments (the score) is as follows:

1 x 12″ Pork Pie snare drum

1 x 13″ Pearl snare drum

1 x 12″ Rancan chinese cymbal

1 x 6.5″ toy cymbal

1 x 6.5″ Cast iron pot lid

1 x 4″ Coin dish

1 x Beaker t-shirt

1 x ciat-lonbarde Fourses (Electric Whisks)

1 x Fender Deluxe amplifier

1 x Ernie Ball volume pedal

This is what the piece looks and sounds like:

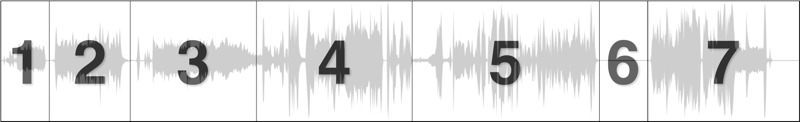

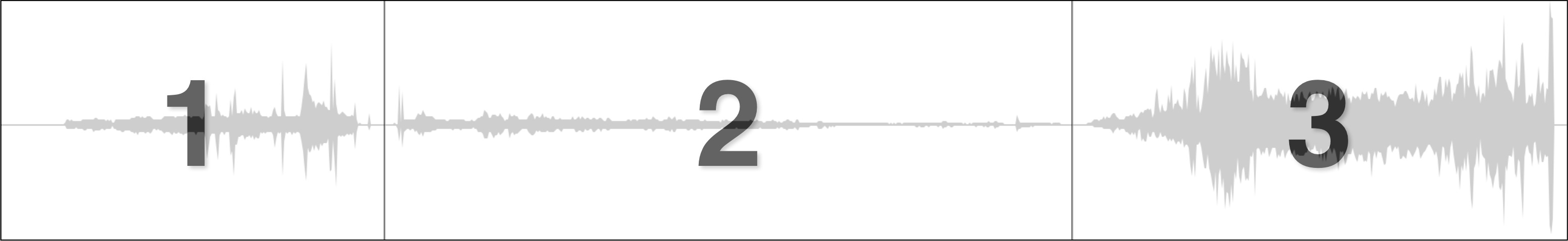

In order to set up and contextualize some of the decision stream analysis I will begin with a formal analysis. Everything (1a) is 3:30 minutes long and can be broken down into roughly seven sections of varying lengths. The longest section (5) is 48 seconds long and the shortest (6) is 12 seconds long, with the rest of the sections (apart from a short introduction) averaging 34 seconds in length.

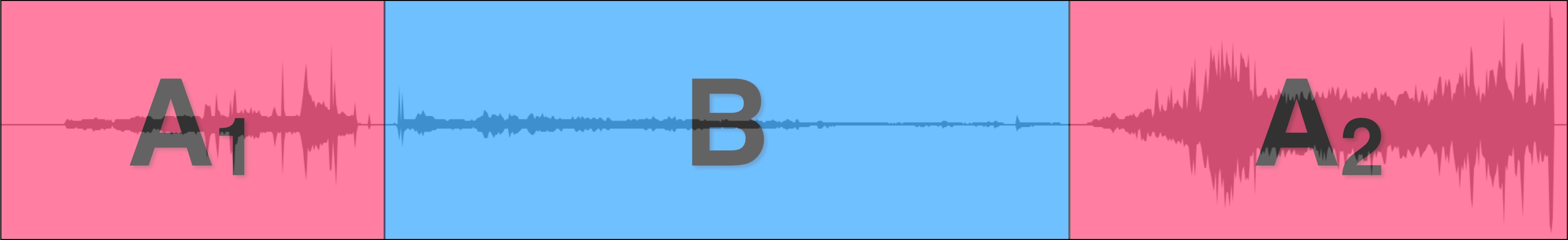

These sections are comprised of an introduction, a transitional section, and several formal blocks of material. I have labeled the introduction as i and the transitional section in the middle as x. The formal blocks of material are labeled as A and B with the section ending the piece labeled as A+B since it is made up of both materials.

The introduction primarily consists of turning on the Fourses/electronics and getting ready to begin performing on the drums. The A section consists of (ir)regular rolls on the drums/objects and is generally preceded by a short period of silence. The B section focuses on the Fourses/Electric Whisks and as a result is more electronic in its content.

The large scale form of the piece breaks down roughly to AABA A+B, or an extended ternary form. The analysis will focus on these formal blocks of material to hopefully identify patterns and tendencies in the decisions found therein.

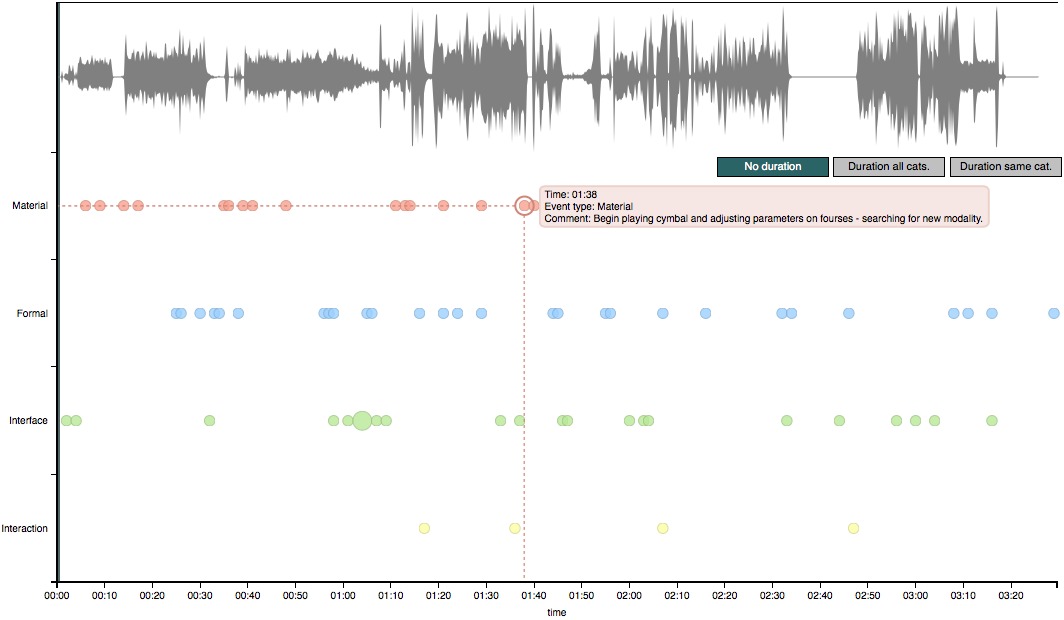

Turning to the decision streams analysis, here is the decision constellation view for the whole piece:

On a surface level there are some remarkable things in this analysis. Most notably, Material decisions stop halfway through the piece, when the sonic material shifts towards being more electronic. This comes along with an increase in activity in the Interface/Interaction streams. The general activity in the Interaction stream is very low (only 4 instances), which could be due to the performance being a solo improvisation as well as the general percussion-heavy approach taken during the piece. Material and Formal decisions are somewhat periodic, interjected with gaps of inactivity, with Formal decisions being the most consistent throughout the performance.

Aside from the opening Interface decisions, the decision types appear in a Material->Formal->Interface->Interaction order, which seems to imply a decision hierarchy where Material decisions are the foundation that the rest of the decision types are based on. This could also explain the disappearance of Material decisions halfway through the performance, as by then the Material exposition has already taken place, and from there on out the established materials carry on through other decision streams.

The overall rate of activity is high, with a total of 70 decisions over the course of the three and a half minute improvisation, coming to an average of a decision every 3 seconds. This is a higher rate of activity than any other analysis I’ve done but this fits with the generally dense/busy material of the improvisation. Additionally this rate of activity is not dissimilar to the average rate of speech, supporting my hypothesis about language and Material decisions being tied together.

Activity Summary

Transition Matrix

Duration stats per stream

Looking at the metrics we can see that Formal and Interface decisions have the most instances in this performance, with Material decisions coming in just below that. The duration between events (rate of activity) in the Material stream, however, is the lowest, signifying a denser and more periodic consideration in this stream. The transition matrix shows Formal->Formal being the dominant transition type, with Material->Material and Formal->Interface being the next most common transition types. This is as expected given the rate of activity in those streams and supports the hierarchical model of streams hypothesized earlier.

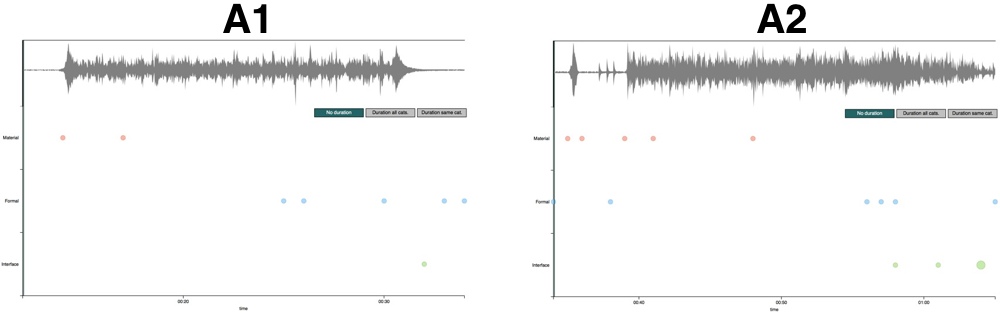

Within each formal section there are some interesting patterns that emerge. Here are sections A1 and A2:

In addition to both being made up of the same kind of dense/percussive material, both of them contain patterns in their decision orders. Both blocks begin with Material decisions followed by more Material decisions as the improvisational language/material is established and developed. Formal decisions begin a bit past the midway point in preparation for the next section/block. Each section then concludes with Interface decisions, as the instruments/electronics are manipulated, that generally follow through on the preceding Formal decisions.

As posited earlier, this pattern of Material->Formal->Interface makes sense in a conceptually structural and hierarchical sense. Musical material is established and developed, then after a while some kind of formal change is conceived (while material events/decisions are still occurring), and finally physical and instrument-specific actions are carried out to move these changes forward. This (conceptual) pattern could be applied to many types of musical and structural developments, improvised or not.

It’s important to re-emphasize at this point that this is a purely improvised performance. Other than the selection/curation of instruments and the creation of an initial preset on the Fourses there were no decisions made ahead of time. So all of these decision patterns emerge from the improvisation itself and signify a real time unfolding of short scale and long scale musical decisions. This decision patterning, I suspect, is intrinsic to the making-decisions-IN-time nature of improvisation, since decisions regarding form/structure generally need to happen while performing.

The B section of material follows the same overall pattern, although with more Interface decisions occurring during the initial Material section.

Decisions dealing with Interaction finally begin in this formal block, coinciding with the introduction of purely electronic sounds and manipulations, and continue through the next several sections. As stated above, this lack of activity in the Interaction stream fits with the solo context and largely monophonic instrumental approach of this given performance.

The general activity level, on all streams, slows down throughout the course of the piece. This is something that has been consistent among all the analyses I have done and received. This perhaps has to do with a process of material and physical exhaustion/saturation occurring throughout the course of an improvisation in a general sense or through an arrival at a state of flow, but more analyses/data will be required before any solid conclusions can be made here.

The ending of the piece sees a near reversal of the Material->Formal->Interface pattern seen earlier. I conclude by interacting with the Fourses, making decisions based on its output, and finally taking formal decisions regarding the ending of the piece. Ending on this pattern, moving through the established stream hierarchy in reverse, is an interesting anomaly and could represent a conceptual closure, although it was not premeditated.

This in-depth analysis of the decisions and streams for Everything. Everything at once. Once. (1a) offers a deeper insight into my general improvisational tendencies and underlying creative processes in a solo electro-acoustic context at the time of filming. The nature of the instruments and approach used prioritized certain decision types (Material/Formal/Interface) and de-emphasized Interaction.

The high activity rate throughout the piece supports my thesis that Material decisions are tied to language, while the overall activity rate’s deceleration suggests a phenomenon regarding decision saturation/exhaustion over time. These hypotheses will be further developed and tested over the course of several analyses, from various performers, to see if these links to language and saturation are general improvisation phenomena or specific to my own improvisations.

The appearance of a decision stream hierarchy (Material->Formal->Interface->Interaction) and the structural decision patterns of Material->Formal->Interface and its near inversion Interaction->Interface->Formal demonstrates how decision stream transitions relate to formal blocks of material in an improvised context. This hierarchy and patterning functions as a structural subtext or punctuation with regard to the formal material and its sounding results.

Analysis 2 – Pierre Alexandre Tremblay – Bass + Laptop improvisation (1)

The next in-depth analysis will be of Pierre Alexandre Tremblay‘s (PA‘s) Bass + Laptop improvisation (1) performance. PA often performs with an electric bass, both as an audio and control source, going into a laptop. In this performance, which was filmed specifically for this analysis, PA uses an iPad running Lemur along with a SoftStep foot controller, augmented with an expression pedal, to control custom software written in Max. The bass goes into an analog distortion pedal and then a volume pedal before plugging into a soundcard, giving PA control over the signal before it enters the laptop.

Here is a picture of his typical setup:

And a close up of the objects/preparations:

Similar to the analysis of Everything (1a) I will begin with a formal analysis. PA’s performance is 6:03 minutes long and can be broken down into three main sections. The shortest section (1) is 1:30 minutes long and the longest section (2) comes in at 2:41 minutes. The final section (3), being 1:52 minutes long, is slightly longer than the first section.

Although there are some smaller sections within these blocks of material, for the purposes of this analysis I have labeled them as A and B.

The opening A section is primarily made up of noisy/textural material. Half way through the opening section bass harmonics are introduced before returning to the noisy material. The B section which follows it contrasts the material in the A section by focusing on slowly moving melodic material in the upper register of the bass. The final A section is similar to the opening of the piece in its intensity, but it is louder, and incorporates a low drone, tapped by the left hand, underneath.

The overall form of the piece, similar to Everything (1a), is an ABA form. Within this ternary form there are more transitions and crossfades of material than there were in Everything (1a)’s block form and the upcoming decision stream analysis will focus on these transitional shifts within the large-scale form.

Firstly, here is the decision stream analysis overview of the whole piece:

Looking at the decision stream overview there are some remarkable things. The first is the amount of general activity before any sound is made. PA begins his analysis by checking multiple aspects of his setup before finally beginning with a Material decision at 16 seconds. The presence of these preparatory gestures/decisions is likely due to the nature of the video/performance being purpose made for this analysis. Another striking aspect is the amount of drastic shifts in overall density throughout the progression of the performance, something that will be explored further in this analysis.

Throughout the performance there are many simultaneous or near-simultaneous events taking place. The first of these happens at 24 seconds and is made up of Material->Interaction->Formal->Interface decisions. This is followed very shortly after by pairs of events at 27, 30, and 31 seconds, which are made up of Formal->Interaction, Material->Formal, and Interface->Interaction, respectively. These areas of busy, multi-stream events could be related to the planning/preparation/execution of multi-dimensional shifts in material.

The rate of activity over the course of the video is high, with 123 decisions happening over the course of 6:03 minutes, which comes to an average of a decision just under every 3 seconds (2.95). The overall rate of decision making is tied to the musical density, with the opening section of the piece containing most of the decisions in the piece. This shift in decision making density suggests a strong link between the decision making apparatus and the type of material it is being used to produce.

Activity Summary

Transition Matrix

Duration stats per stream

Through the metrics we can see that the most active decision streams are Formal and Material, with Interface decisions being the next most active. The median time between events in the Interaction stream is the lowest, whereas the Formal and Material streams are similar in their activity rate. The transition matrix shows Interface->Material being the most common transition type, with Formal->Formal, Formal->Interface, and Material->Formal happening equally as often. Given the overall activity in the Formal stream, both in terms of the amount of decisions and the time between them, the predominance of Formal->* transitions is to be expected.

The opening A1 section is made up of noisy/textural material that gradually increases in dynamic before being layered and interrupted with natural harmonic chords on the bass. Once the material is set in motion the activity in the decision making streams slow considerably, only to pick up in preparation for the first loud harmonic chord at 1:05. There is a second sustained bass chord at 1:11 that interrupts the noisy/textural material, which is accompanied by a lull in decision making.

This performance contains an interesting musical anomaly where PA has a large technical problem. At 1:22 PA inadvertently unplugs the bass when trying to hit another clean harmonic chord. What follows is a flurry of anxious activity in almost complete silence while PA tries to troubleshoot and then resolve the problem in the middle of the performance. The comments during this section are worth reading in a performance psychology kind of way since PA manages to resolve and carry on in spite of a large technical failure. Also remarkable is how quickly PA switches back to making musical decisions once he plugs the bass back in at 1:33.

Activity log

During the B section the material shifts drastically towards a sustained pad/chord which is overlaid with melodic material in the upper register of the bass. After some initial decisions relating to the establishment of new material the decision stream slows down drastically, in a similar manner to the A1 section. The decision rate increases again at 2:32 once PA begins planning for the next formal block. These spikes in activity function as structural anchors similar to the decision patterns (Material->Formal->Interface) found in the Everything (1a) analysis.

The A2 section returns to louder/noisier material which builds towards a sudden stop. At the beginning of the section we see an instance of the decision pattern (Material->Formal->Interface) that was prevalent in the Everything (1a) analysis. This is followed by a spike in activity leading towards the shift in texture at 4:46. Also present in this final section is the inversion of the structural decision stream pattern (Interface->Formal->Material), although here it leads towards the setup of the final moment, rather than the final moment itself, which is in this case a single Formal decision.

As has been the case with every analysis I’ve done up to this point, the rate of activity slows over the course of the piece. This is the case for all the streams combined as well as the individual streams. What is interesting for this particular performance is that there is an increase of activity once the A2 section begins, but even that bump in activity level still accords with an overall decrease in activity.

The working hypothesis I put forward in the Everything (1a) analysis is that this decrease in activity stems from an exhaustion/saturation taking place during the performance, but this could also perhaps be due to an exhaustion/saturation during the analysis process itself. In order to rule out this possibility I will create some analyses from performances where performers are directed to consciously increase their rate of decision making over the course of the piece to see if the analytical trend remains.

Creating an in-depth analysis of PA’s performance has provided offered a deeper understanding into his general improvisational tendencies and how he approaches his hybrid setup. The processing and layering heavy nature of the approach used in this video accounts for its having more active Interface and Interaction streams than most of the other analyses done up to this point. The stream hierarchy established in the Everything (1a) analysis (Material->Formal->Interface->Interaction) is still present in this analysis, as is the active and periodic nature of the Material stream, supporting the hypothesis that activity on this stream is tied to language.

Shifts in musical material from the A to B sections are accompanied by changes in overall decision stream density. This correlation between musical material density and underlying decision stream activity is evident in and is of particular significance to this performance. Each formal block has a decision stream density which clearly matches the musical material contained within it.

In addition to the established patterns of Material->Formal->Interface decisions there are spikes in activity that function as structural anchors. These underpin the changes in material found at the beginning and ending of sections as well as occasionally appear as part of the setup/planning for the next section. Given the in-time nature of improvisation in general it is interesting to see where the performer places these pre-formal spikes in activity and how they negotiate the mental juggling of the current and next in a musical context.

These in-depth analyses of Everything (1a) and PA’s Bass + Laptop (1) performances provide a richer understanding of the decision making apparatus across multiple performers. Using the framework and analysis tools in this manner, specifically with embedded/dynamic examples, shows some of the general usefulness of the system in a musicological context. The insights gained from the analyses will be incorporated into the future developments of the system, which include automatically looking for specific patterns, structural segmentation, and shifts in material/decision density as well as a general refinement and application of these concepts into the conceptual framework and accompanying terminology.

Tangential Analyses – Upright Citizens Brigade / Triadic Memories

The inclusion of the analysis of an Upright Citizens Brigade (UCB) ASSSSCAT! performance is intended to demonstrate the use of the system in a non-musical context. Comedy improvisation, specifically long-form comedy improv, is intensely about decisions. No statement by a player (performer) is made without having some kind of consequence in the scene (Besser, Roberts, and Walsh 2013). Everything a player says either heightens, explores, or advances (in time, location, or stakes) the narrative that is being established. Additionally, since “exposition sucks”, as stated by long-form improvisation guru Del Close in explaining why all scenes should “start in the middle”, the scenes begin immediately (Halpern 1994).

The scene that I analyzed (buzzards) was chosen for three main reasons. The first reason is that it is a well-documented performance, filmed using multiple cameras with lapel mics on each performer. The second reason is that three of the members of the UCB (Matt Besser, Ian Roberts, Matt Walsh) have done an audio commentary on the performance, giving their own thoughts and insight into what is happening within the scene. Their commentary is fascinating and worth listening to even outside of the context of this analysis. The final reason is that this group scene demonstrates several clear games and interactions that can be understood outside of the context of the long-form show.

To create the analysis data I transcribed the entire scene and treated each line as a discrete decision/event. Since nothing is said without consequence, as can be seen in the analysis data below, this served as the backbone of the analysis data. I then transcribed the UCB members’ commentary and ‘quantized’ their comments by attaching them to the line that they were initially referring to. Since their commentary is recorded in real-time, they will often continue talking about a specific line once its delivery has passed. I then added my own commentary to each line, clarifying some of what is happening in the context of the scene. So each analysis point has the following format: player comments – [UCB comments] – {my comments}.

Click here to view and interact with the Upright Citizens Brigade’s ASSSSCAT! analysis.

The most tangential of all the analyses I’ve done is Bryn Harrison‘s reflective listening of Feldman‘s Triadic Memories. The idea to create such an unusual analysis came from a conversation with composer John Lely where we were talking about the improv analysis system/idea. John told me about Richard Glover and Bryn Harrison’s book Overcoming Form, specifically Bryn’s chapter on Triadic Memories, and suggested that it might make for an interesting analysis for the system.

Triadic Memories is a long (circa 70 minutes) solo piano piece typical of his works of the era. The piece is made up of sprawling self-similar blocks of material where “the sheer incomprehensibility of this work through the intentional confusion of memory” serves to disorient the listener’s relationship to the material and time itself (Glover and Harrison 2013). This means that by definition my analysis would give insight into Bryn’s perceptual apparatus, which is something that the system wasn’t originally designed for, but may be well suited to.

The unusual nature of the analysis approach (a technical analysis of a listening analysis of a fixed composition that deals with disorientation) as well as the poetic notes themselves meant that I had to take a different approach to creating the analysis data. Some of Bryn’s notes refer to specific moments which I was able to attach a clear time stamp to: “Now a change in register as the highest notes descent by an octave”, “And now the pitches change [G, Gb, F]”. There were other notes which were much more nebulous and difficult to quantify: “I feel, temporarily, like I have arrived somewhere, but where?”, “I do not wish to recall past events but to savour the moment”. I created a spreadsheet for tracking the more concrete key frames which I used to interpolate the time stamps for the events between them. This approach, although not ideal, would at least generate a large-scale consistency in the data that removed my own interpretation from the equation. In this way I produced an analysis of the first 26 minutes of the piece, stopping only where the text becomes too poetic to extract any useful timing information.

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

The Future

There are many updates and improvements in the works for the 2.0 version of improv analysis. The first of these, which is already in progress, is the building up of a database of analyses from myself and other performers. I have asked several improvisers I regularly perform with, as well as other local and high profile improvisers, to contribute analyses. I hope to build up a database of at least 20-30 analyses before incorporating some of the more complex improvements discussed below in order to assess the system/framework across a variety of genres and approaches to improvisation.

The existing/core visualizer with be refined and improved with the inclusion of additional features and graphics. The waveform display will be consolidated with an inline video player, allowing you to see the performance in context with the decision streams (not unlike the comment system in the Soundcloud player seen below). Some of the metrics, such as the transition matrix, will be included into the constellation chart, allowing for the visualization of that material in a more meaningful way. Similar contextual visualizations will be generated for the static min/max/mean calculations.

[su_pullquote align=”right” class=“”]This will allow a higher order structural analysis to take place.[/su_pullquote]

One extension to the existing reflective analysis will be the inclusion of formal/structural highlighting via the user interface. The performer will be able to segment the improvisation into formal sections as well as label any recurring materials, similar to what I created for the analysis of Everything (1a) in the section above. This will allow for a higher order structural and contextual analysis where decisions made within sections of (recurring) material can be compared.

Eventually, the system will include a page where one can upload their own analysis files (a .csv file, an mp3, and an optional link to a video file), and the system will automatically add it to a database of existing analyses. The user will then be able to view their own or any other analysis in the database. Building up a database of performances in this manner will allow for some useful metrics to be calculated for each performer and give perspective on the overall tendencies within communities of improvisers.

Once I have enough data, I, with the help of Tom, will come up with additional graphs and metrics to aid the correlation of data between analyses. The system will include the ability to correlate analyses in one-to-one, one-to-many, and many-to-many relationships, allowing for a rich and complex set of visualizations.

[su_pullquote align=”right” class=“”]I plan on analyzing duo and trio improvisations by having each performer analyze their own performance blindly to be able to correlate data from within a performance.[/su_pullquote]

In addition to the analysis and correlation of solo performances, I plan on analyzing duo and trio improvisations by having each performer analyze their own performance blindly to be able to correlate data from each performance within the same performance. I will perhaps expand this to include the perception of ‘back-channeling’, or nonverbal cues, as outlined in this paper by Moran et al. to add a secondary layer of correlatable data. This will, undoubtedly, provide tremendous insight into the group dynamic and interplay happening between performers. This multi-entry analysis type will also be able to be correlated against other analyses in the database, providing further calculations and accompanying insight.

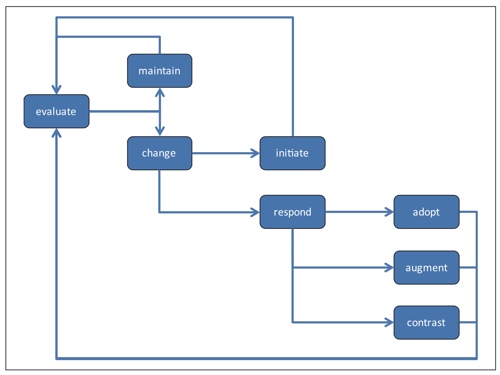

Model for the process of individual choice during group musical improvisation.. Chart from Wilson/MacDonald

The approach used by Graeme Wilson and Raymond MacDonald in this paper, which focuses on in-depth interviews with the analyzed improvisers, introduces interesting qualifiers to moments of transition. Their findings show how performers, working in trios, would either adopt, augment, or contrast their material based on a cycle of constant evaluation (Wilson and MacDonald 2015). These qualified Formal decisions could be incorporated into my analysis framework, giving a secondary layer to the Formal decision stream.

Along with the improviser-generated reflective analysis I plan on incorporating some automated audio descriptors, feature mapping, and audio segmentation to the system so that your decisions can be auto-correlated to their sounding results and structural divisions using tools like Vamp, Essentia, or Couprie‘s EAnalysis system. This information will be saved along with the analysis data and will eventually be incorporated into the visualization. For the time being this information will serve as offline data which will be used to link into other software tools.

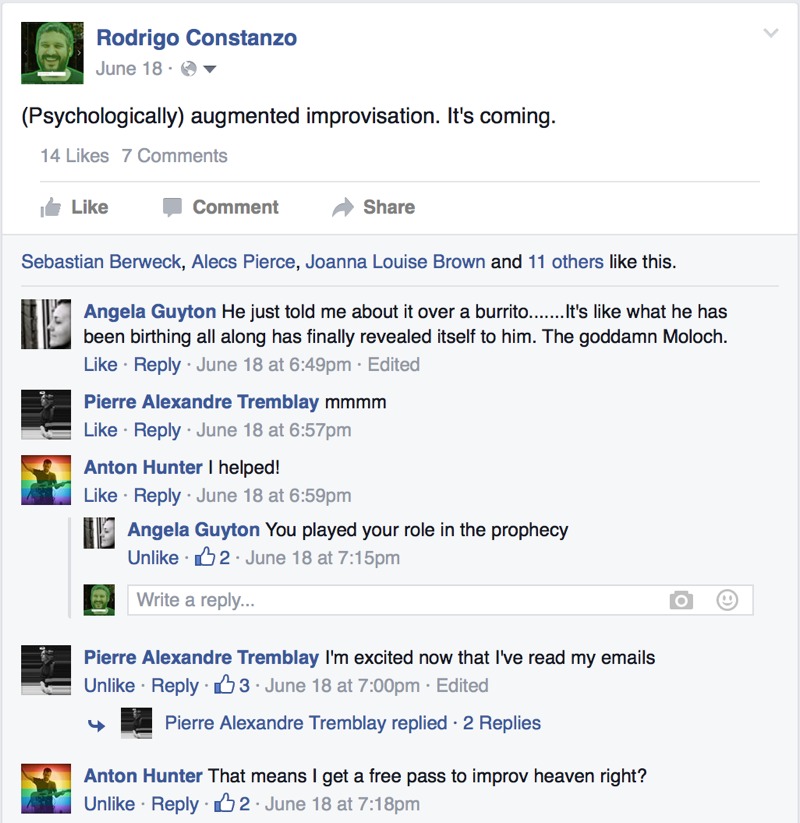

‘The prophecy as foretold’, or ‘How to get into improv heaven’.

The most exciting addition, by far, will be the integration of improv analysis with the dfscore system. The idea to do this stretches back to some email conversations with Alex Grimes regarding his composing of a piece for me on snare/objects with someone live-sampling my performance using Cut Glove. Alex had seen an earlier version of this blog post on the improv analysis framework and was planning on using the data from my analyses that were available on the page. I suggested that it might be interesting to create an inversion of my tendencies to push me outside of my improvisational comfort zone. Some months later in discussion with Anton Hunter about the dfscore system I had the idea that this could be used as a pedagogical tool; the dfscore system could automatically create inversion scores based on single or multiple analyses. This fits in well with the pedagogical motivations of the dfscore system in general.

In addition to creating dfscores for use in an educational context, the same analysis data could be used to algorithmically generate compositions using a definable corpus of analyses. This could not only incorporate the decision stream event types, transition matrices, and timings, but the reflective analysis comments and feature extraction data. I could browse through the analysis database and select analyses by myself (or others) and use that to seed a variety of compositional algorithms (Markov Chain, Neural Network, Evolutionary, etc…) in order to create meta-compositions based on the characteristics of multiple improvisations/improvisers. Curating this analysis corpus would be similar to defining a sonic corpus for use in concatenative synthesis (C-C-Combine) and represent another refocussing of a meta-creative practice.

Combining improv analysis and dfscore has interesting implications for the manipulation of creative agency as a creative parameter, similar to the focus on decision streams using the improv analysis framework. Using a database built up from your own previous improvisations and then making decisions, possibly in real time, about how much of your existing tendencies, or their inversions, you want to perform with is an intriguing idea. Much more so if it is coupled with predictive real time analysis based on correlated audio feature extraction; a psycho/techno-logically augmented improvisation where you can receive prompts, in real time, about possible decisions to make while improvising based on your previous experiences, interactions, and tendencies, creating a “dance of agency” (Pickering 1995).

That’s the [improvisational, creative, (utopian) futurist, technopositive, augmented, cyborg-ian] future I want to live in!

You can follow the developments of this improvisation analysis framework on its static page here. As I add more analyses, and come up with new approaches on how to visualize the data, I will update the static page, and add any relevant links to it there.